Alchemy & Religion

- Sylvia Rose

- Dec 7, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2024

Alchemy through the ages is a science affected by personal spirituality and religion. Rooted in ancient practices, alchemy takes shape in the religious and metaphysical systems of diverse cultures and epochs. Here are a few historic and modern influences of religion in alchemy.

Influence of religion on alchemy through history is an intriguing story of historical evolutions and cultural frameworks guiding practitioners. Alchemy involves transformation of matter through processes such as distillation, alloying, sublimation, dyeing and calcination.

The emphasis on transformation becomes a soul quest in the early centuries AD. The first known alchemist, Mary the Jewess of Greco-Roman Alexandria, is a practical alchemist. She explains how to alloy metals and achieve diplosis, or doubling of gold.

Through Mary, four colors of alchemy, black, white, yellow and red, come into use inspired by Greek artists of the time. They would place their palettes, containing those basic colors in a wax medium, over a small brazier to keep them fluid.

Mary uses these colors to explain the progression of a copper treatment. However they've found their way into later alchemy in a highly spiritualized fashion. She also uses the concept of the brazier to invent the kerotakis, an important piece of equipment in practical alchemy.

In spiritual or speculative alchemy the quest for the philosopher’s stone is a prevalent cliché even today. Lapis philosophorum first appears in writing in 14th century Europe, though offhand references to various rocks go back to philosopher Democritus in the 5th century BCE.

Mysticism in alchemy is highly influenced by Islamic practitioners after the conquest of Egypt 642 AD. Spirituality is distinct from religion, and alchemy absorbs it all. Here are a few religious practices with creative influence on the work of alchemy.

Hermeticism

Hermeticism, derived from the teachings attributed to legendary Hermes Trismegistus, merges elements of Greek, Egyptian, and Christian thought. Central to Hermeticism is the belief in the correspondence between the macrocosm (the universe) and the microcosm (the individual).

Hermes Trismegistus is a combination of Egyptian god Thoth and Greek Hermes, emerging from the pagan religions of the ancient world. In the context of history Hermeticism is not as ancient as it first appears.

Hermeticism initially proposes the concept of God as a magician. This idea emerged from texts translated in the late 1400s by Ficino in Florence, Italy, known as the Hermetic Writings or Hermetica. They're purported to date from c. 300 - 1200 AD.

The writings are said to be by an ancient prophet, Hermes Trismegistus. The principle "As above, so below" is foundational in alchemy, attributed to Cleopatra the Alchemist of Alexandria in her work Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra.

It's often re-attributed to Hermes, specifically the Emerald Tablet of late antiquity. The original Chrysopoeia is lost and the remnants of today are Islamic copies. The Ouroboros or snake with tail in mouth is a common alchemical symbol.

Hermetic texts, such as the Corpus Hermeticum, provide alchemists with philosophical frameworks combining spiritual and material realms. In this way, some alchemists feel they are legitimizing their experiments as part of a divine cosmic order.

The Emerald Tablet is a foundational Hermetic text. It emphasizes unity and the divine relationship between humans and the cosmos. For spiritual seekers, alchemy becomes more than metals and herbs, creating pathways to understanding the divine within.

Renegade Renaissance physician Paracelsus is a proponent of the Seven Hermetic Principles.

Gnosticism

Gnosticism, an early Christian sect characterized by its dualistic worldview, profoundly impacts alchemical thought. Gnostics believe in achieving spiritual enlightenment through knowledge (gnosis), often seen as secret or mystical insights.

Many alchemists adopt the idea, expanding their work to include personal transformation and enlightenment theories. The Gnostic text The Gospel of Truth (c.140-180 AD) posits the belief of understanding and transcending the material world is a precursor to divine knowledge.

This emphasis on inner transformation resonates with alchemists seeking self-purification and spiritual ascension. Alchemical texts of the Gnostic tradition often use symbolic language, linking material reactions of substances to allegories of the soul's ascent to divine knowledge.

Many Gnostics, such as Zosimos of Panopolis c. 300 AD, are ascetics, shunning pleasures of the world. His treatises stress the importance of foundational truth. Zosimos is among the most prolific Alexandrian alchemical writers and practitioners, revered by later Islamic alchemists.

Gnosticism reshapes alchemical thought. Gnostics emphasize personal spiritual knowledge, believing physical matter is a flawed reflection of a higher, spiritual truth. The universe is a battleground between materiality and spiritual enlightenment.

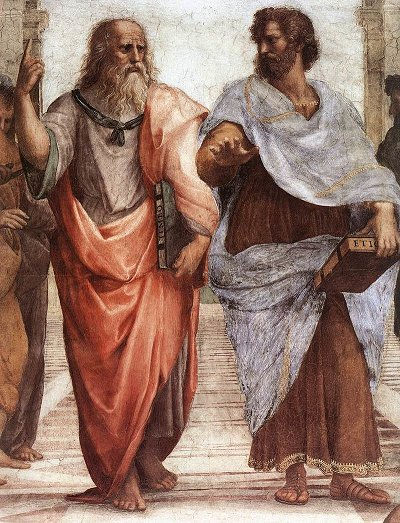

Neo-Platonism

Neo-Platonism emerges in the 3rd century AD. It introduces metaphysical ideas and heavily influences alchemical thought. Emphasizing the notion of an ineffable One from which all existence emanates, Neo-Platonism advocates for the soul's return to this divine source.

Some alchemists adopt this framework to conceptualize their work as a means of achieving spiritual enlightenment and unity with the divine. The transformative process in alchemy reflects the soul's journey towards divine knowledge and union.

Neo-Platonism asserts a connection between the material realm and the ultimate reality, referred to as the One. This perspective invited alchemists to see their laboratory work as a route to reconnecting with the divine source.

This philosophy influences many throughout the Middle Ages, as some alchemists align their work with a greater metaphysical purpose. Neo-Platonism appears in both Christian and pagan forms. Early proponents include Stephanus and Hypatia of Alexandria.

Islam

During the Islamic Golden Age, alchemy soars with the influence of Islamic scholars. Figures like Jabir ibn Hayyan (Geber) synthesize earlier Greek, Roman, and Arabic alchemical knowledge, integrating it with Islamic teachings.

Islamic alchemy emphasizes the pursuit of knowledge as a form of worship, viewing the material world as a reflection of God's creation. At the time of the Islamic Golden Age, the mythical philosophers' stone is not yet known.

Up to the 10th century Islamic alchemists believe in the maturation of metals in the ground, disproved by Avicenna. At this time they cease pursuit of precious metals and focus on metaphors for spiritual renewal and enlightenment, aligning closely with Sufism.

Islamic alchemists believe understanding the universe is essential to comprehension of divine will. Writings of Jabir ibn Hayyan greatly influence later alchemists, emphasizing the enduring legacy of Islamic thought and the mystic allure of the East in alchemical practices.

Judaism

Jewish mysticism, particularly Kabbalah, significantly contributes to alchemical thought. Kabbalistic teachings explore the relationship between the divine and the material, emphasizing the concept of Tikkun Olam (repairing the world).

Alchemists draw parallels between their transformative processes in science and Kabbalistic notions of creation and spiritual elevation. The use of sacred names and symbols in both practices link Jewish mysticism with alchemy in a quest for physical and spiritual well-being.

Concepts like the Sefirot, which represent divine aspects, informed Jewish alchemical practices. Jewish alchemists pursue applications in medicine.

The Kabbalistic alchemist Isaac Luria (1534 - 1572) puts forth theories about divine sparks in all matter. This view inspires later alchemical experimentation. Luria suggests healing processes can restore both physical and spiritual balance.

Of course the first known alchemist is Mary the Jewess, also called Maria the Jewess, and Maria Prophetissa around the 16th century in Europe. Raphael Patai (1910 - 1996) thoroughly describes the history of Jewish alchemy in his writings.

In The Hebrew Goddess (Patai 1967) the author argues that historically, the Jewish religion has elements of polytheism. He stresses the idea of the worship of goddesses and a cult of the mother goddess.

Buddhism

Buddhism stresses the quest for enlightenment and the concept of transforming the self through discipline and meditation. Some sects within Tibetan Buddhism incorporate elements of Tantric practices aimed at achieving spiritual realization and enlightenment.

Buddhism's emphasis on inner change resonates with alchemical thought, particularly around the idea of personal transformation. Rather than seeking material transmutation, Buddhist principles encourages practitioners to focus on self-improvement and spiritual development.

Alchemical processes are thus seen as allegorical representations of personal growth. The Buddhist doctrine of impermanence aligns closely with the alchemical cycle of dissolution or decay and rebirth. Buddhism sees transformation is an essential part of existence.

Hinduism

Hindu texts and theories, such as the concept of rasa (elixir; mercury) and siddhi (spiritual knowledge, success), have influenced some alchemical practices in India. The practice of alchemy, rasa-shastra (mercury manual or rules), is a way to achieve spiritual enlightenment.

Unlike the gold-obsessed Europeans, alchemists in Hindu traditions aim to attain immortality or enhance life. This is often interpreted as a parallel to the alchemical quest for the mythical philosopher's stone.

Alchemical practice in Hinduism combines physical practices with philosophical and spiritual objectives rooted in the belief in divine consciousness. In Hindu lore, amrita is the elixir of life.

In the sacred Puranas, two power hungry groups battle it out. Due to the defeat of the devas at the hands of the asuras, preserver deity Vishnu tells the devas to churn the ocean of milk, so they may retrieve amrita to empower themselves.

In Hinduism, the cyclical nature of life and the universe informs alchemical principles. The beliefs surrounding creation, preservation, and destruction influence practices. Alchemical purification is often seen to parallel a spiritual quest for higher consciousness.

Taoism

Taoism profoundly impacts alchemical practices in China. Taoist alchemy seeks to achieve immortality and harmonize with the Tao, or the fundamental principle of the universe.

Transformation within this context further develops inner alchemical processes leading to the quest for spiritual illumination and unity with the cosmos. The Taoist pursuit of the elixir of life shapes Imperial Chinese history, literature and philosophy.

Chinese alchemy predates Western alchemy by several hundred years. In the 3rd century BCE Qin Shi Huang becomes first emperor of united China. He employs court alchemist and magician Xu Fu to seek out the elixir of life.

Taoism introduces the duality of yin and yang, emphasizing harmony between opposing forces. This philosophy is fundamental in Taoist alchemy, guiding practitioners to balance energies both in the lab and in life.

Taoist alchemists pursued immortality through internal cultivation rather than relying solely on substances. This holistic approach shaped alchemical practices into a comprehensive lifestyle, where bodily health and spiritual well-being are interconnected.

Christianity

There are many kinds of Christianity and many kinds of alchemy. Christian influence on alchemy is most pronounced in the Middle Ages, with many alchemists being clerics or deeply religious. Christianity infuses alchemy with symbolic interpretations of biblical texts.

The alchemical process can be seen as a metaphor for spiritual salvation and ascendance of the soul. The concept of resurrection is likened to alchemical transmutation of substances, with the mythical philosopher's stone becoming a symbol of Christ's redemptive power.

Christianity re-interprets or claims common symbols such as the Pelican, a flask given the name because its handle(s) resemble a pelican preening. In Christian iconography the pelican becomes a symbol of sacrifice because it tears open its breast to feed its young with blood.

Christian alchemists in medieval Europe adopt the concept of self-sacrifice associated with the pelican flask and bird. Many have never seen a pelican and depend on the information of the day.

The interplay of alchemy and religion happens on a broader scale of seeking divine truth through material experimentation. Many alchemists view their work as a way to explore God’s creation and help humanity, legitimizing their practices within a religious framework.

Prominent alchemists, such as Ramon Llull and Roger Bacon integrate Christian theology into their works. Older writings are translated or re-written to include spiritual interpretations, praises and prayers, further solidifying the bond between faith and alchemical practice.

One strongly religious fire and brimstone alchemist is Jean de Roquetaillade, also a Franciscan friar. He writes about the Apocalypse and the coming new world order. HIs predictions include societal collapse, human extinction and other final events in human history.

Alchemists occasionally enter a monastery because these places have the best equipment due to brewing practices, and large libraries. While many practitioners belong to a holy order, others are "honorable" members and still others are known to opportunistically switch orders.

Christianity is an important influence on alchemy. Especially in medieval Europe, failure to align science with God is heresy. A famous example is Polish polymath Copernicus, who refuses to publish his theory of a heliocentric universe until he's on his deathbed.

While he's not noted as an alchemist, the plight of Copernicus affects all sciences at this time. During the Renaissance and early modern era in Europe, the split between practical alchemy and spiritually-focused alchemy becomes one on the greatest divides in the history of science.

By the 18th century alchemy has acquired a scurrilous, non-scientific reputation due to fraudsters and those who promise what they cannot deliver. Dropping the "al", chemists strive to distance themselves from alchemy's bad rap.

The truth of alchemy lies with the ancient Alexandrians. Here we arrive at the end of one cycle, and the beginning of another.

Non-Fiction Books:

Fiction Books:

READ: Lora Ley Adventures - Germanic Mythology Fiction Series

READ: Reiker For Hire - Victorian Detective Murder Mysteries