Bronze Age: Ancient Afterlife & Burial Beliefs

- Sylvia Rose

- Oct 27, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2024

Afterlife beliefs affect burial practices of the Bronze Age. The Bronze Age emerges at various times cross-culturally, such as Indus Valley c. 3300 BCE and China c. 2000 BCE. Cultures like Egypt, Mesopotamia, Indus and Yellow River develop complex civilizations and burials.

People of high rank or esteem of course have more elaborate burials. In ancestor worship several days of rituals and reverence to honor the dead, avoid a curse of bad luck.

Some cultures favor simple coffin-like inhumation, often in tumuli or hills of earth and stone. Ornaments, weapons, clothing, personal items, even servants and musicians, might be buried with the corpse.

A tumulus of Neolithic times is made of layers of habitation, as each generation builds upon the ruins of the previous. The Neolithic tumuli often include corpses placed in walls, under floors, in pottery jars or nooks and crannies. At this time people literally live with the dead.

Above: The Dilmun Civilization flourishes in ancient East Arabia for thousands of years. A prosperous trade center, Dilmun eventually declines due to factors including piracy on the sea routes.

Dilmun is described in the saga of the Sumerian myth Enki and Ninhursag as a paradise. Predators do not kill, pain and diseases are absent, and people do not get old. 19th century scholars consider its potential as the biblical Garden of Eden.

In Egypt, natural desiccation is observed in the desert. Mummification includes such rituals as organ removal (expect the heart), treatment with preservatives such as cinnamon, myrrh and tarry bitumen. The body is rubbed inside and out with the natural salt natron and left 40 days.

During this time rites and worship take place. Pharaohs are honored with vast tombs and rich burial items to facilitate their mystic journey. The body below is lower on the social ladder, mummified in a flexed position often found in burials, and having modest grave goods.

After the natron treatment of Pharaoh or noble, the cleansed organs are wrapped and placed in the body cavity. The body is wrapped in strips of linen, which also hold amulets and spices.

This work is done by the priests. It's important for the well-being of the deceased to keep the body as whole as possible. If not the deceased has no intellect, is clumsy and cannot communicate with the gods.

Over the Bronze period in China (beginning c. 2000 BCE) graves evolve considerably. From simple earthen vertical pit tombs with a few pottery vessels they grow into multi-chambered underground or hillside tombs furnished with silk, jade, bronze, lacquer, clay and bamboo.

Chinese jade is usually white or creamy. Green jade is a later product of Myanmar (Burma). Jade is valued for its longevity, musical properties, and aesthetic appeal. Its delicate, translucent hues and protective attributes connect with Chinese ideas of soul and immortality.

In China, prior to the spread of Shang and Zhou culture throughout the area, the Baiyue people of the Yangtze Valley and southeastern China build many hundreds of tumuli. Throughout the world these burial methods are used both by high and lower social classes.

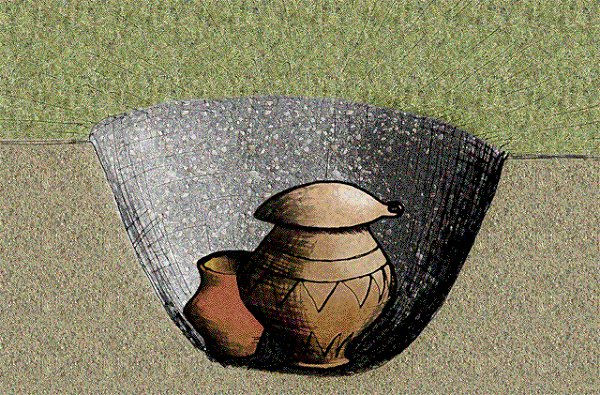

Burial mounds contain the grave, deceased and burial items such as pottery, personal artifacts, metals like copper and gold. Occupation of the deceased might be shown with items like dyes or tools. Some Mesoamerican cultures use vermilion (cinnabar) in graves.

Many early people have no specific belief in an afterlife but honor the dead with a funeral of feasting, feats of strength, fights or athletic games. Others embark on complex traditions of ancestor worship.

In the case of the walking undead of Germany or others who rise from the grave, measures to keep the dead contained include rosemary or caraway sprinkled on and around the burial site. Herbs like rosemary, caraway and cinnamon are also known insect repellents.

In herbology lore, rosemary banishes evil spirits. Caraway protects against malevolent magic. In Mesopotamia it's important to libate the ancestors through a pipe to the grave, to avoid unwanted hauntings. Talismans interred with the corpse also keep the dead from wandering.

In the variable settlements and thick forests of north and central Europe, evil spirits lurk in the wild hills and crept around homes at night. Malevolent people can throw curses. As early as12,000 BCE people use or wear ornaments of protection against harmful forces.

The Chinese culture of the Yellow River, c. 11,000 - 3000 BCE, usually bury their dead in coffins inserted into hills. Artifacts of stone, copper and later bronze such as drinking vessels and urns might be buried with them.

The best place to bury a person in ancient China is near the water. Water has strong associations with portals and the spirit world across many cultures and time periods. Spiritually water is also linked to intuition, harmony and wealth.

In China, ancestor worship is popular from c. 6000 BCE. Mourning periods can last up to three years. In folk religion, a person has dual souls. Hun and po correspond to yang and yin. When a person dies, hun and po separate.

Hun ascends to heaven and po goes into the earth and/or lives in a spirit tablet. The number of souls can vary. Separately, distinct practices arise to accommodate perceived needs of the dead. In China white and yellow chrysanthemums symbolize death and grief.

In the Indus Valley of South Asia, civilization lasts from c. 3300 to c. 1400 BCE. The culture goes through dynamic changes but funeral customs are simple. The dead person is wrapped in a shroud and buried in a coffin, possibly in a tumulus, with head pointing north.

Again, items of wealth or personal use is found in burial sites. From the Indus Valley Culture come early developments in metallurgy to produce and work with copper, bronze, lead, and tin.

In the Bronze Age, personal items almost always accompany bodies, often including copper or bronze utensils and weaponry. Their purpose is based on speculation. Are these to help the dead in the spirit world? Or are they to keep the dead from haunting the living?

In Egypt, a tomb dating back to 3rd millennium BCE contains inscribed instructions to the pharaoh, his wives and various members of the nobility and elite about navigating the land of the dead. These rituals are for royalty and the very wealthy only.

If a powerful Pharaoh dies, he becomes the God Osiris and is worshipped in this form. His son assumes the role of a living God to rule the land. Osiris relates to agriculture, death and resurrection.

Also in the 3rd millennium, Minoan culture sprouts on the Greek island of Crete. Funerary practices are similar to those observed in Egypt, Mesopotamia and among Steppe nomads. The body is interred, sometimes in an engraved coffin of rank, along with personal items.

Around 2000 BCE, cremation is a common choice. Is it due to the population explosion happening at the same time? The occupants of the known world have less space to share with each other, and with the dead.

Partly or fully cremated remains are found in large urns. In ancient Greece, funerary ashes are kept in painted Lekythos vases. Cremation and grave burial dominate at different times and places in history, often occurring in cycles.

Behind burial beliefs and practices, tribal Bronze Age cultures have a fundamental belief system or cosmology involving elemental Gods such as the Earth Goddess or Mother Earth; the Sky God; the Sun or Dawn God/dess.

Earth is the origin of life and the body's final dwelling place. Mythology expands and adapts with appearance of fire gods, weather gods, gods of tradespeople, gods with jobs such as gatekeeper; gods of the hunt, herds and agriculture, or patron gods of specific regions.

As mythology broadens so does the view of spirits, the dead and associated rites, rituals and protocol. Gods of the Dead and Underworld come to life.

The necropolis or City of the Dead develops as civilizations age and coalesce. A necropolis is more than a graveyard. Some even have roads, gardens, decorations, habitations, friendly neighbors, offerings and gifts, everything the dead might need.

Ancient cities such as Memphis, Egypt develop the necropolis to its furthest level, including the building of the Pyramids of Giza. They're part of a complex of tombs, passages and burial sites extending over 30 km (19 mi) west of Memphis.

The Egyptians choose the west for the City of the Dead because it's the direction of the sunset, while east represents life or new life with the sunrise. In ancient Egypt, the soul has three to nine parts.

One is Ba, the impersonal life force of the soul, or essence of a person's individual nature and unique characteristics. The second is ka, the quintessential spirit, which makes a being alive. Finally the akh is the transformed spirit who survives death and takes a place with the gods.

Non-Fiction Books:

Fiction Books:

READ: Lora Ley Adventures - Germanic Mythology Fiction Series

READ: Reiker For Hire - Victorian Detective Murder Mysteries