Glass & Arts of Ancient Glass Making

- Sylvia Rose

- Aug 3, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Nov 28, 2024

Glass production is known before the Bronze Age. Early glassmakers in Egypt and the ancient Near East produce colored beads and later utensils. Alchemical Alexandria is a glassmaking site c. 1st century AD. Later Italian Renaissance glassmaking takes the art to new heights.

Natural glass forms in quickly cooled conditions such as volcanic lava pouring into the sea or extruding through the slope. The first plentiful natural glass is obsidian, found in volcanic zones. East of the Black Sea, a Neolithic obsidian processing center operates c. 9000 BCE.

Other types of natural glass include moldavite, thought to come from the impact of meteorites; and Libyan desert glass created by a bolt of lightning fusing sand with sudden intense heat.

The art of glassmaking goes back to c. 3800 BCE. Based on archaeological finds, the first genuine synthetic glass is crafted in regions like Lebanon, coastal north Syria, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt. Glass is a heat interaction of sand, lime and soda ash.

The earliest glass artifacts are primarily beads, potentially originating as accidental by-products of metalworking (slags) or during the production of Egyptian faience, a glass-like material created through a process similar to glazing.

Early glass is often non-transparent, containing impurities and flaws. Red-orange glass beads are uncovered from the Indus Valley Civilization, a culture known for carnelian beadwork, dating pre-1700 BCE.

The first glass production relies on methods borrowed from stone working. The maker grinds and carves glass while it's cold, just as in carving clear quartz or rock crystal. The jug below is from Renaissance Italy, a time when ancient art and wisdom is re-discovered in Europe.

An early glass-forming method involves working molten glass around a clay or sand core. The mold is heated and the molten glass fuses around it, leaving a hollow. This creates a container for everyday use.

Glass items from molds are all made a similar way. The mold can be graphite, silicone or metal. Molten glass is poured into the mold and left to harden. Once hardened, it's removed from the mold. Extra glass in the middle is scooped out and remelted later.

Continuous glass production starts c. 1600 BCE in Mesopotamia and 1500 BCE in Egypt. In the Late Bronze Age, major advances in glassmaking occur. Discoveries from this era include colored glass ingots, vessels, and beads.

By the 15th century BCE, significant glass production happens in Western Asia, Crete, and Egypt. The Mycenaean Greek term ku-wa-no-wo-ko-i, translating to "workers of lapis lazuli and glass" is documented.

The knowledge and techniques needed for initial glass fusion from raw materials are a closely guarded secret. Consequently, glassworkers in other regions have to rely on imported pre-formed glass.

The Bronze Age collapse of c. 1200 BCE halts glass production. It starts again in Syria and Cyprus, c. 9th century BCE, with discovery of techniques for producing colorless glass. The oldest known glassmaking "manual", cuneiform inscriptions, dates to c. 650 BCE.

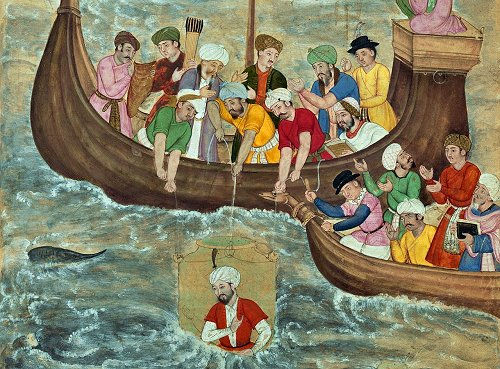

Diving bells, described by Aristotle in the 4th century BCE, are major advances in underwater exploration and engineering. Aristotle's student Alexander the Great has a glass diving bell made. It's said he descends to scope out enemy positions in the Siege of Tyre 332 BCE.

Glass-making is reintroduced in Ptolemaic Alexandria, Egypt (323 - 30 BCE). While core-formed vessels and beads remain popular, new techniques emerge due to experimentation and technological advancements.

Glassblowing is invented by Syrian craftsmen around Sidon and Aleppo in the 1st century BCE. Blown vessels are created for everyday and luxury use. Produced commercially, they're exported to all parts of the Roman Empire.

It looks easy but takes time to master the art of glassblowing. An artisan inserts molten glass onto a hollow metal tube and blows through the tube to create a glass bubble. After the bubble is made, workers use tools and flat surfaces to shape and design the glass.

Throughout the Hellenistic era, various innovative glass production methods are introduced, leading to creation of larger items such as tableware. Techniques such as 'slumping' involve shaping viscous glass over a mold to create dishes or specialized alchemical apparatuses.

Alexandria is known for its medical schools in the Ptolemaic period as well. Physicians such as Hippocrates study in Egypt. Glass is perfect for medical experiments. Alchemy and medicine are closely linked and many doctors are also alchemists even into the Victorian Era.

In the 1st century AD, the industry experiences swift technological advancement with the innovation of glass-blowing and the prevalence of clear or 'aqua' glasses. The production of raw glass and the crafting of finished vessels were carried out in different geographic areas.

By the end of the 1st century AD, extensive production, mainly in Alexandria, leads to the widespread availability of glass as a common material in the Roman Empire. 1st century alchemist Mary the Jewess enthuses over the glass vessels and invents a few too.

The term "glass" originates in the late Roman Empire (284 - 641 AD), from a Roman glassmaking hub in Trier, Germany. The substance is known as "glesum," referring to a clear, shiny material.

Roman glass artifacts are found throughout the Roman Empire in homes, burial sites and areas of industry. Like faience, glass is a desirable item of trade. Roman glass appears in such diverse places as China, the Baltics, the Middle East and India.

According to Pliny the Elder, Phoenician traders are the first to stumble upon glass manufacturing techniques at the site of the Belus River. Georgius Agricola, in De re metallica, reported a traditional serendipitous "discovery" tale of familiar type:

"The tradition is that a merchant ship laden with nitrum [niter] being moored at this place, the merchants were preparing their meal on the beach, and not having stones to prop up their pots, they used lumps of nitrum from the ship, which fused and mixed with the sands of the shore, and there flowed streams of a new translucent liquid, and thus was the origin of glass."

History says glass arrives on the scene before Phoenicians, but it's a good story. Pliny also believes rock crystal is ice frozen so long it's become stone. However he's the first to discover amber is a resin. With Pliny it's kind of hit and miss.

To keep glass malleable enough to work with, hardened glass is heated in a furnace. Glass melts at 1,400 - 1,600 °C (2,552 - 2,912 °F). Artisans heat the glass until it's pliable; then the maker manipulates and crafts the material to desired form.

Once the glass has been shaped and designed, it is removed from the furnace and left to cool slowly at room temperature. This cooling process is crucial to ensure that the glass retains its structural integrity and does not crack or shatter due to sudden changes in temperature.

The Romans excel in creating cameo glass, a technique of etching and carving through layers of fused colors to create raised designs on glass objects. Glass is used extensively in Europe during the Middle Ages.

From the 10th century on glass is used in stained glass windows of churches and cathedrals. By the 14th century, architects design buildings with walls of stained glass.

During the Renaissance, glass making is dominated by powerful families in Italy. The most famous glass comes from Murano, an island in a chain off Venice. By the 13th century it's dominated by a podesta or magistrate from Venice.

By 1291, all glassmakers in Venice are told to relocate to Murano. Over the next century, exports start, leading to the island's renown, particularly for glass beads and mirrors. Again, the formula for glass making is kept a secret, forcing dependence of pre-made products.

Murano's glassmakers are soon among the island's most prominent citizens. By the fourteenth century, glassmakers are permitted to wear swords. They are immune from prosecution by the Venetian state, and their daughters marry into Venice's most affluent families.

Aventurine glass is first created on Murano. A translucent glass with sparkling inclusions of gold, copper, or chromic oxide is first made in Venice in the 15th century. This establishes Venice as Europe's primary glass producer for several centuries.

Subsequently, the island gains recognition for exquisite glass chandeliers. Despite a decline in the 18h century, glassmaking remains the primary industry of Murano.

Non-Fiction Books:

Fiction Books:

READ: Lora Ley Adventures - Germanic Mythology Fiction Series

READ: Reiker For Hire - Victorian Detective Murder Mysteries